Courtesy of the Ty Cobb Memorial Baseball Collection.

by: WESLEY FRICKS, National Ty Cobb Historian

Tyrus Raymond Cobb was by far the greatest player in Major League Baseball’s history, but very few write about his personal side—the side that has been buried beneath the weight of time.

Cobb died on the afternoon of July 17, 1961. It was at that point when dime-store writers finally had their way with Cobb and his legacy – the great player and personality in the game.

Today, I would like to share with you some things that have been misinterpreted by these writers, bloggers and the Internet down through the years. The one that stands out most is the assault that writers and websites of today have placed on Cobb’s relationship with blacks and minorities.

I will carefully explain the facts and let you come to your on conclusion.

As I have recognized a need to present those facts about Ty’s relationships with blacks and minorities, I have decided to write a story that displays Ty Cobb’s support for blacks and other minorities, and among other personal stories of his relationship with other people.

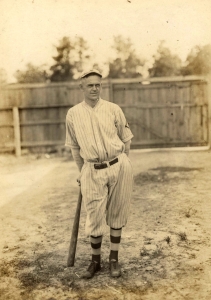

Courtesy of the Ty Cobb Memorial Baseball Collection.

It is important to provide facts, supporting the reality that the negative publicity came after Cobb died in 1961. I also enclosed several articles, and interestingly, one that I found where his son, Jim Cobb, made the exact same assessment in 1977 that all this negative stuff was part of a craze of the 50’s and 60’s to publicize negative stories to boost attention and sales.

My readers, if you were to research the facts, you’ll find that Mr. Cobb was different than he is portrayed in the eye of the modern press and instant mediums, websites and blogs. He was rich with popularity, and writers back then could always count on his name to generate interest in their newspaper and today a negative crafted blog story can catch on faster that one of Walter Johnson’s fastball on a good day.

Mr. Cobb was a charitably-natured man, who actually was soft for the minority, whether the minority was someone who had different colored skin, or handicapped, someone who was less fortunate, or even someone who was small in size.

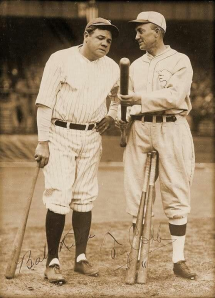

Courtesy of the Ty Cobb Memorial Baseball Collection.

He would always tell the little fellow that was standing in the back and could not get close to come to the front. He wanted to make sure they got a chance, too.

In the late 1920s, Ty Cobb leased a hunting preserve with over 12,000 acres in MaGruder, GA, and built a house on it for a black man, named Uncle Bob and his family to live there.

In place of the rent, they would make sure no intruders trespassed on the property. Anytime Cobb and his friends were hunting on the land, this fellow, by his own choice, would always hunt along beside Cobb. At times, he would entertain the guest with his story-telling.

After a long day of hunting, they would gather around a campfire and talk baseball or whatever came to mind. On this particular day, Cobb had bagged 12 birds and had not missed a one, as Mr. Cobb was a crack shot.

Uncle Bob told the story to Tris Speaker and the others, “Yeah, Mr. Cobb had a bad day today.” “What do you mean, Cobb bagged 12 birds and didn’t miss,” said Speaker. “Yeah, but he near ‘bout missed one,” recounted Uncle Bob.

Present-day authors have distorted Cobb’s reputation to a point of the ridiculous. For example, the book COBB, which the movie COBB was based on, tried to show that COBB hosted orgies and drinking parties.

I have the contract agreement on the land, and it clearly states that there was to be “absolutely NO alcohol on the premises.”

This was at Major League Baseball’s Brunswick, GA retreat. It was called “Dover Hall Club” and Ty Cobb was one-sixteenth part owner of the 2,500-acre hunting and fishing camp.

The MLB magnates owned it from the early 1910s until the late 1930s. Cobb was the only player of the sixteen investors that bought into the $1,000 stock-leasing plan.

Mr. Cobb was in financial straits in the spring of 1906, but by the end of 1907, he had worked and saved his money. He began investing it in real estate in Georgia. In 1908, he bought 15 acres in Toccoa, GA and built and remodeled some of the nicest little homes in a predominately black neighborhood.

He named the subdivision “Booker T. Washington Heights,” and financed these homes to these residents for a minimal amount.

He owned the property until 1940, and he turned it over to his son, Herschel Cobb, to assist him with starting him a Coca-Cola franchise in Idaho. One transaction sold a lot (No. 22) to J. H. Johnson for only $42.50 in 1909. It was a relatively good price, even for that era. There were 109 lots in Booker T. Washington Heights.I hear a great deal about Cobb’s racism in the present, especially on the Internet, but no one ever has actually have provided factual or even specifics about their racial allegations. If Cobb had been a racist, some newspaperman would have made remarks about the specifics in some way.

I have over 40,000 newspaper articles, and NOT one article makes any correlation to Ty Cobb being a racist. All the evidence demonstrates Cobb’s support for the advancement of colored people, and yet, there is NO evidence that gives any indication that Mr. Cobb made any movement toward oppressing the black population.

Contrary, when Jackie Robinson entered into the major leagues, it began a slow process of allowing blacks to begin entering into every league in the country. When the Dallas club of the Texas League was considering allowing blacks to enter, Cobb was there to bat for them.

Courtesy of the Ty Cobb Memorial Baseball Collection.

“Ty Cobb, Fiery Diamond Star, Favors Negroes In Baseball”

Independent Journal—Jan. 29, 1952

MENLOPARK (AP)—Tyrus Raymond Cobb, fiery old-time star of the diamond, stepped up to the plate today to clout a verbal home run in favor of Negroes in baseball.

Himself a native of the Deep South, Cobb voiced approval of the recent decision of the Dallas club to use Negro players if they came up to Texas league caliber.

The old Georgia Peach of Detroit Tigers fame was a fighter from the word go during his brilliant playing career. He neither asked for nor gave quarter in 24 tumultuous years in the American League. Time has mellowed the one time firebrand and he views the sport in the pleasant role of a country squire. He spoke emphatically on the subject of Negroes in baseball, however.

“Certainly it is O.K. for them to play,” he said, “I see no reason in the world why we shouldn’t compete with colored athletes as long as they conduct themselves with politeness and gentility. Let me say also that no white man has the right to be less of a gentleman than a colored man, in my book that goes not only for baseball but in all walks of life.”

“I like them, (Negro race) personally. When I was little I had a colored mammy. I played with colored children.”

Referring again to last week’s developments in the Texas league, Cobb declared, “It was bound to come.” He meant the breaking down of baseball’s racial barriers in the old south.

Cobb expressed the belief Negroes eventually would be playing in every league in the country. He concluded with: “Why not, as long as they deport themselves like gentlemen?”

Article courtesy of the Associate Press.

Courtesy of the Ty Cobb Memorial Baseball Collection.

Ty Cobb did have an altercation with at least four African-Americans during his lifetime, but I have all the documents from these incidents, and in every case, the problem can be traced back to an action, unrelated to racism, that was committed by Cobb himself, the black person, or a third party, which caused the issue to escalate into an altercation.

Remember the black butcher incident of 1914 that caused Cobb to play in only 96 games? His racism was so bad that he beat up the butcher just because he was black? Well, the fact is that the butcher, Harold Harding, was a white man and the brother-in-law to William L. Carpenter to whom he lived with and helped to run the meat market. After Ty Cobb died, these authors concocted the story to make Cobb look more like a demon and a racist. Remember that these were the years leading up to desegregation and race relations were at their peak. To make Ty Cobb look like a racist was a sure seller in the early 60’s.

I am not going to discourse tediously on whom was at fault in either of the other incidents because I only want to exhibit that there was a reason that the incidents happened that had nothing to do with color. And I must mention that Cobb’s incidents with whites far exceed the number of occurrences with the blacks.

Ty Cobb was not a racist, he did not sharpen his spikes to slash other players just to steal a base, he did not kill a man in Detroit, as alleged by recent fabricating, nickel writers, and he did not live the life of a bigot. Contrary to those myths, Ty Cobb exerted a kindness toward blacks and lived a great life.

One of his fondest memories of his youth was being taught how to swim by a black laborer named Uncle Ezra. Ezra would get young Ty to cling to his neck and wade out into the middle of the river or stream. At this point, Ty would be released and forced to swim back to the riverbank.

Blacks lived in Cobb’s house behind his home on Williams Street there in Augusta. Cobb employed blacks the whole time he lived on the “Hill”. Emaline Cosey lived with and worked for Ty Cobb in 1920.

Jimmy Laniergrew up in Augusta with one of Ty Cobb’s sons. Jimmy has told a story many times about Herschel and himself, going to the Rialto Theatre in downtown Augusta to see one of them ‘shoot’em up’ movies. “We came out of the theatre and Mr. Cobb, like a father, was waiting on the other side of the road,” claimed Lanier.

“As we were getting into the car, Mr. Cobb overheard the owner of a nearby restaurant explaining to a man dressed in shabby clothes how to get to the Linwood Hospital—a veterans hospital. Mr. Cobb interrupts and says, ‘Son, I’ll take you there.’

“The man stood on the running board of Mr. Cobb’s La Salle coupe, and they were talking back and forth, and this man was a veteran of World War I. When they pulled up to the gate at the Linwood Hospital, I saw Mr. Cobb hand this man a $20 bill. Herschel was looking off at somewhere else, but I saw what Mr. Cobb done. It was incidents like this that never made it to the press,” concluded Lanier.

Friends, I believe that one of Mr. Cobb’s problems was that he never looked for credit for anything that he done. He could never boast of his philanthropic nature that would put celebrities like Babe Ruth or Joe DiMaggio on the crest of publicity. And two, he never refuted accusation against him publicly.

If someone alleged that he had spiked another player intentionally, he gave an explanation only to the person or people that it mattered to most, like owner of the Tigers or President of the American League, but very seldom to the press.

If he would have stood up and said to people, “You are wrong,” or, “That is not true,” maybe these present-day authors would have had less room to reinvent his reputation to their own liking.

Ty Cobb was a close associate to the second commissioner of baseball, Albert B. “Happy” Chandler, who was head of the baseball realm when Jackie Robinson entered into Major League Baseball.

Cobb was a big supporter of Chandler. In a press interview on Aug. 30, 1950, Cobb shared his support for Chandler, “So far, Chandler has lived up to everything that I thought he could do as a commissioner. To me, every one of his decisions have been fair.”

The article goes on explaining Cobb’s support for “Happy.” Three years later, he was elected to serve as member of the Board of Trustees of the Cobb Educational Foundation.

The Foundation contributed $2,800.00 in scholarships the first year. 50-years later, and the annual grants have reached well over $500,000. As of July 2003, the Foundation has provided scholarships to 6,876 students, equaling $9,743,000.

Thanks to his charitable nature, Ty Cobb has made it possible for thousands of students of Georgia to achieve a higher mark in education. There is no limit to what this Foundation can provide to future students who truly want an education. One thing is certain; it is bound to generate a winning team of students in this great state of Georgia.

And as I mention frequently, I could go on forever, talking about great things that Mr. Cobb did to enrich the lives of other people. He did this without any expectations from the recipient or others that witnessed his philanthropic deeds.

In an interview in the mid-1950s, Mr. Cobb made this statement, “You’ve ask me about this Cobb Educational Fund, and now I’m going to have to answer it. I do not wish to be eulogized for what I have done. I’m proud of it, yes. This Educational Fund has given me the greatest possible happiness and pleasure, and maybe when I’m gone we’ll have some real great men developed out of the Cobb Educational Foundation.”

Ty Cobb Healthcare Systems, Inc. provides jobs to thousands of healthcare professionals in northeast Georgia, and I know, personally, a young black fellow that I went to school with that works for the healthcare system and has made a huge impact on the community.

He got his start at the Cobb Memorial Hospital and now is a providing leadership in the direction of the city.

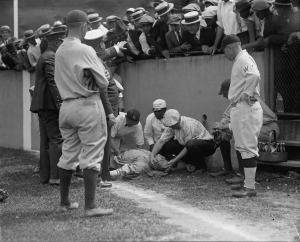

Courtesy of the Ty Cobb Memorial Baseball Collection.

Ty Cobb’s father was a Georgia State Senator from the 31st District, who voted against a bill introduced and approved by the Senate that allowed taxes deriving only from black properties to finance the black schools. This was in 1900.

He stated in the Atlanta Constitution that the, “Negroes had done, and were doing a good deal for the up building of the state, and I am in favor of allowing them money for education.” He believed that the race should be protected from class legislation.

In 1950, Cobb dedicated the new hospital in Royston, GA to provide medical attention to the region. In Dr. J. B. Gilbert, Cobb found one of the finest African-American doctors to serve the black population, and this was before desegregation.

Dr. Joseph B. Gilbert, M.D. Courtesy of the Ty Cobb Memorial Baseball Collection.

Dr. Gilbert also serviced white patients and later became Chief of Staff at the Cobb Memorial Hospital. Dr. Gilbert’s daughter remembers Ty Cobb visiting the home when she was just a young lady. Cobb signed baseballs for all three of Dr. Gilbert’s grandchildren.

In 1953, Cobb established the Ty Cobb Educational Foundation to give scholarships to needy students in Georgia. Hundreds and hundreds of young black students have become a beneficiary of this educational fund.

Alec Rivers was a black employee of Cobb for 18 years and named his first-born Ty Cobb Rivers. “Even if it would have been a gal, Ah would have named her the same,” Rivers relayed to his friends in an interview with The Detroit News.

Rivers served as Cobb’s batboy, chauffeur, general handyman, and was an avid supporter of the famed “Georgia Peach.”

After 22 seasons with Detroit, Cobb joined the Philadelphia Athletics to finish out his 24-year career. Rivers followed Cobb, “I wasn’t exactly against the Tigers, but I still had to be for Mr. Ty.”

Ty Cobb’s racist reputation came only after he had died in 1961. Racial reform should not be fought at the expense of a man who helped make baseball a great sport for colored people to enjoy, too.

Cobb loved Augusta! He did not just live there for a while—it was his home. He raised all of his children there. He lived at 2425 William Street in the Summerville district. He held common and preferred stock in the Augusta Chronicle. He sold Hawkeye trucks there in the Augusta area.

He was president and principle owner of the Ty Cobb Tire Co. on Broad Street. He owned the Ty Cobb Beverage Co., who had their office at 313 in the Leonard Building. He was one of three principle owners in the City Bank of Thomson.

He hunted and fished in all parts of the Augusta area and even down the Savannah River. He was on the Board of Directors of the First National Bank in Lavonia, GA for all his professional life.

He coached and umpired some at the Richmond County YMCA and in the Nehi League. He entered his girls into beauty pageants, horse shows, and musical recitals. He helped the city authorities host outside guests.

When a large group of Philadelphian businessmen came to Augusta, Cobb participated in a first-of-its-kind aeroplane golf tournament for the visiting spectators. Cobb owned a great deal of property in the city.

One piece of land was 444.72 acres south of Spirit Creek and the Augusta Orphan Asylum.

Mr. Cobb owned the properties on the east side of Tuttle, between Fenwick and Jenkins Streets, corner of Broad and Seventh (McIntosh), 10 acres, five miles out on old Milledgeville Rd., two lots on the corner of Druid Park and Gwinnett Street, southwest corner of Twiggs and Boyd’s Alley containing five lots, four lots close to the corner of Phillip Street and Walton Way, and Cobb’s property list goes on and on.

Looking over the Richmond County Court documents, it appears to me that in some cases, Cobb loaned money to help prevent foreclosure on some of the properties.

He lived adjacent to a dentist that started the South Atlantic League back up after it shutdown during the depression. Eugene Wilder worked as secretary to the Mayor of Augusta for many years and was an admirer of Cobb’s.

Captain Tyrus R. Cobb, United States Army Courtesy of the Ty Cobb Memorial Baseball Collection.

When Cobb entered the United States Army in 1918, he left Dr. Wilder instructions and money he had set aside for his famous prize dog, ‘Cobb’s Hall’, in case he failed to return from the war. Cobb served as a Captain in the Chemical Warfare Division over in France at the close of the war.

Cobb also became part owner of the Augusta Tourist in 1922. The team name was later changed to Augusta Tygers to honor Cobb. He developed many young athletes into strong competitors.

He managed the Detroit Tigers from 1921-1926, and during that time, a Detroit batter won the batting title four out of six years. He was a great teacher, and he loved to devote his time to helping others advance.

Ty Cobb was always concerned about the advancement of the city of Augusta. He was always striving to promote and stimulate the city’s economy. He donated his vehicle to the fire station to be auctioned off.

He owned numerous businesses in Augusta and drew people of every nature to the city. He once hosted the sole owner of the Diamond Tire Company, who came down from up north. There were a couple of Presidents of the United States that Cobb became acquainted with on the streets of Augusta.

In closing, I just want to say that all these little things add up to give us plenty of reason to say that Cobb deserves being memorialized with the facts.

I was involved recently with the naming of the Augusta Stadium and the race issue was brought forward. “But I can’t sit and allow people to say such negative remarks such as ‘Cobb was a racist’ without at least trying to educate the public on the absolute truth,” I told several of the Augusta Commissioners.

I recommended the stadium be named “Cobb Memorial Stadium,” or something that would commemorate the great Georgia athlete. “Georgia Peach Stadium” may have been a happier medium that could have satisfied both sides of the debate.

At any rate, my position is only to educate and pass on the information that is sometimes forgotten or unknown. I hope that I have provided you with enough information to give you a different perspective on who Ty Cobb really was as a man and as a legend.

This is only a speck in the sand of the material that I possess on this great athlete. I would be happy to assist anyone, in any capacity, to tell the factual story about the game’s most prolific hitter.

I hope that the reader has been enlightened and receptive to this information, and I hope that it will assist them in the reconstruction of his or her opinion of Ty Cobb. I want to leave you with words straight from Ty Cobb’s own quote.

“I like them, personally. When I was little, I had a colored Mammy. I played with colored children.”

TY COBB Museum, Royston, Georgia Courtesy of the Ty Cobb Memorial Baseball Collection.